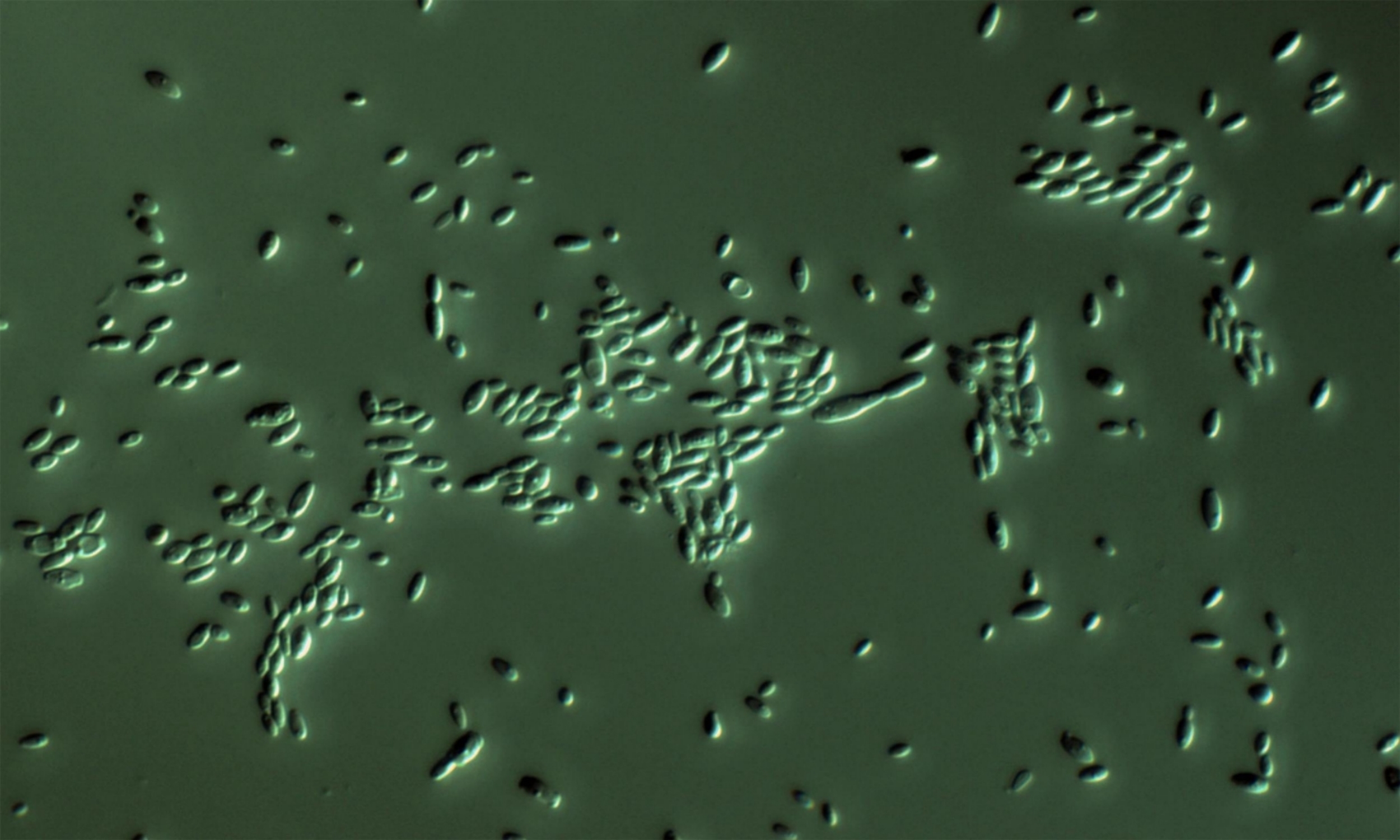

Brettanomyces is a genus of yeast, also known as Dekkera. It has been known for about a hundred years as being an important component in British and Belgian beer styles by adding a unique complexity and sourness. However, when Brett is found in wine it is typically considered a wine fault. Seasoned wine professionals can immediately identify Brettanomyces in a wine by the band-aid, medicinal, horse stable aromas it gives off. However, not many know that there are actually two different chemical compounds that together make up this aroma we vaguely term as “Brett”. This pesky yeast species produces 4-ethylphenol (4-EP), described as band-aid, antiseptic and horse stable and 4-ethylguaiacol (4-EG), which has a rather pleasant aroma of cloves and smoke. These aromas are released in the highest concentrations during the "death phase" (decline) of the population, which usually means it is too late in the cycle for prevention.

Typically, 4-EG is present in much lower quantities in red wine than 4-EP. The concentration of 4-EG in a wine falls between 0 and 300 µg/l , whereas 4-EP has a concentration between 0 and 2300 µg/l. However, 4-EG is a more volatile compound with a sensory threshold at 150 µg/l which is much lower than 4-EP’s threshold at 600 µg/l.

What does this mean? The smokey, clove aromatics associated with 4-EG are present in your wine at a much lower concentration but they are much more volatile than the barnyard, medicinal, band-aid aromatics from 4-EP, which are present at a higher rate. Together both of the compounds influence the perceived “Brett” character in wine. Next time you smell Brett in a wine ask yourself: Am I noticing cloves and smoke or band-aid, barnyard aromatics? These aromatic profiles are distinctly different and to be able to distinguish one from another will be a great advantage.

This graph displays measured concentrations of 4-EP and 4-EG in three wines. In each case,the concentration of 4-EP is fairly consistent. The major difference is the relative concentration of 4-EG. Displayed ratios of 4-EP : 4-EG range from 3:1 to 18:1

There is a significantly greater risk for contracting Brett in wine by using new, toasted oak barrels. Brett feeds off cellobiose, a compound that is formed when barrels are toasted. The yeast prefers new over neutral barrels because there are more sugars available for the yeasts to live on which helps the populations grow. Other factors known to contribute to the growth of Brett include high pH, warm temperatures (above 59 °F), residual sugar, low SO2, poor cellar hygiene, and heavy lees.

Sources:

"Brettanomyces Masterclass with Matt Thomson." Wineanorak. Nov. 2007. Web. 31 May 2016.

"Microbiology: Monitoring Brettanomyces by 4-EP and 4-EG." ETS Laboratories. 5 Jan. 2015. Web. 31 May 2016.

Smith, Clark. "Wines & Vines." Post Modern Winemaking: Integrated Brett Management. June 2011. Web. 31 May 2016.

"Wine Education Topic: Brettanomyces Character in Wine." Aroma Dictionary. June 2004. Web. 31 May 2016.